My dad once showed me a letter from his great (X4) uncle Lorenzo Lyons to his sister Betsey Lyons Miner, my great (X4) grandmother. The letter was dated about 1860 and sent from Hawaii where Lorenzo worked as a congregational missionary. The letter expressed how much he missed his home in Massachusetts and reminded me how privileged I was to be able to live in Sweden and fly over to visit my parents in the US every summer.

I didn’t think much more of it at the time. I had never been to Hawaii, never planned to go, and besides, missionaries in Hawaii don’t have a great reputation, do they?

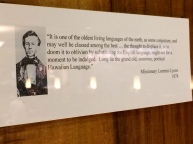

All that changed years later when I waited in the lounge of a Waikiki hotel with my daughter who now calls Hawaii home. I spotted a photo of Lorenzo in an exhibit about missionaries who helped develop a written form of the Hawaiian language. Beside the photo was a quote written by him in 1878:

“It is one of the oldest living languages of the earth, as some conjecture, and may well be classed among the best . . . the thought to displace it, or to doom it to oblivion by substituting the English language, ought not for a moment to be indulged. Long live the grand old, sonorous, poetical Hawaiian Language.”

His words, his respect and admiration for the Hawaiian language told me that Lorenzo did not deserve the bad rap missionaries have had.

I learned from my brother that not only did Lorenzo learn the language, he also wrote songs in Hawaiian, including one that is something of a classic. Hawaii Aloha is sung in Hawaiian and English. The chorus is:

“Happy youth of Hawaii, Rejoice! Rejoice! Gentle breezes blow, Love always for Hawaii.”

The Samoan playwright, John Kneubuhl, wrote a play about his life called The Harp in the Willows, referring to the story in Psalms about the Jews who were captives in Babylonia.

From his arrival in 1832 to his death in 1886, Lorenzo founded and led 14 churches on the island of Hawaii, including the Imiola church in Waimea where he is buried. My sister Carolyn visited the area and described it as “cattle country, complete with lush rolling pastures, cowboys and horses, and big Dodge-Ram pickup trucks navigating the narrow roads.” The dormant volcano Mauna Kea, considered sacred by the Hawaiians, loomed in the background with a fresh cap of snow. She wondered if the landscape reminded Lorenzo of his home in New England.

Imiola congregational church, Waimea, Hawaii

The 159 year-old Imiola church is very Spartan on the outside, but inside the walls, floor, pews and altar were made of the rich reddish-brown Hawaiian koa wood that is known for its lovely swirling patterns. After visiting the churchyard she walked into the village of Waimea and bought some honey from a Hawaiian woman at the farmer’s market. Carolyn asked the woman about the area and got a pithy social and political history from the first settlements (by Polynesians around year 500) through the missionary era (“they demonized the Hawaiian language and culture”), on to statehood (1959) and Obama (“born in Hawaii but not really Hawaiian”). When Carolyn admitted she was there to visit the Imiola church her face lit up. “Oh that is a good church, a Hawaiian church,” she said, meaning it was one of the few churches that embraced local culture and language.

That peaked Carolyn’s curiosity and she decided to return for a Sunday service. Not being a regular churchgoer, she sat unobtrusively at the back and observed as the church filled with about 80 people of different ages and ethnicity, and two dogs. She felt a genuine warmth among the congregation, from the time they entered the church and greeted each other and throughout the service as they interacted with each other, hugged and held hands, laughed and sang. Songs and prayers were projected on a screen with powerpoint (no dusty hymnals here!) in Hawaiian and English. Two women acted out the story of one song with hula gestures. Fortunately for Carolyn, the sermon was in English and dealt with forgiveness, humility and being non-judgmental, themes that my sister could easily relate to and appreciate.

Carolyn left Waimea, and I left the hotel lobby, feeling a warm respect for our great (X4) uncle. Despite his homesickness, Lorenzo embraced his new country and the people and language in it. A review of the play about his life summed it up thus:

“His youthful certainty which was expressed in moral terms gradually disappeared and in its place came the love of a people and a sense of oneness with them.”

Postscript 2015:

Anna, André and I got to Waimea to see the church for ourselves. The church and its setting were truly lovely. For a recent rendition of the hymn Hawaii Aloha look here.

Imiola church with two snow-topped volcanoes

Lorenzo Lyons grave, Waimea, Hawaii

Koa wood interior